By Printus LeBlanc

California is once again on fire. The Mendocino Complex fire, south of Redding and the Carr fire, is now the largest wildfire in California history. The blaze is giving firefighters trouble, as it has leapt across barriers, natural and man-made, burning more than 280,000 acres so far. Many were quick to point to the blaze as evidence of global warming because apparently global warming is the cause of everything. But the environmental radicals do raise an interesting question, why does this keep happening out west?

The short and sweet answer is, the environmental policies pushed by the environmental radicals have contributed to and made forest fires out west much worse.

Forest fires were a common sight in the early 20th century. The fires were numerous and large. The available data from National Interagency Fire Center shows the 1920s and 30s were the toughest years out west. From 1926-1929 there was an average of over 140,000 fires per year, burning over 270 acres per fire. The 1930s saw over 180,000 fires per year while burning 218 acres per fire. From the 1940s through the 1970s the average size of fires continued to drop with the 70s being the low point at only 21 acres per fire.

The sheer volume and size of fires in the early 20th century is easy to explain. The west was still sparsely populated, and firefighting had not advanced, technologically or tactically enough to make a difference. Two things happened in the 50s to change all that. First was the westward movement of the population. Returning service members decided to move out west instead of remaining in the overpopulated east.

The second thing to happen was Smokey Bear. In 1944, the Smokey Bear campaignwas rolled out, followed in 1947 by the slogan “only you can prevent forest fires.” The campaign gained more recognition after a bear cub was caught in a 1950 New Mexico fire. The poor cub was badly burned and used as a national symbol for the fight against forest fires.

The combination of more people, better technology, and an advertising campaign had a real impact. So much in fact, that the average number of fires per year in the 1970s was 15 percent less than the 1950s and the size of the fires were reduced by an astounding 83 percent.

Then the environmental movement happened. The number of fires continued to decrease, but the size of the fires started to grow. So much so, that from 2010-2017, the average size of a fire increased over 400 percent, to 102 acres per fire. What happened?

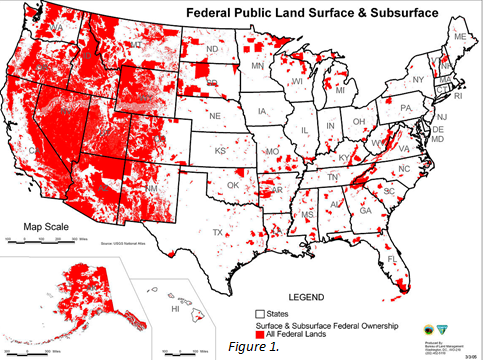

The first problem is who is in control of the land. The federal government controls the majority of the land west of Texas. Federal rules and regulations have made it next to impossible remove dead trees, infected trees, and dry underbrush. That is all fuel for a fire. When a fire starts on unmanaged federal land, it doesn’t stop at the fence line or city limits. That is why the fight must be to stop the fires before they happen by denying a small fire the fuel to become large and creating breaks to stop a fire once it starts.

As William Stewart, a forestry specialist at the University of California at Berkeley, told the Washington Post in relation with the recent wildfires, “the rates of mortality from fire, insects, and disease are about three times as high on national forest lands as they are on private lands regulated under California’s strict environmental laws.” Whether the regulations on private land play the vital role there is another matter. The fact is, the underbrush and dead trees are being cleared on the private lands, but not the federal lands.

One only has to look at the map of federally controlled land in the western U.S., figure 1, to understand the problem. There are just as many forests in eastern Texas, Arkansas, and the Appalachian Mountains as there are in the west. The plains are nothing but highly flammable grass. The only difference is the amount of control the federal government has on the land.

Land owned privately is taken care of for a simple reason, profit. If someone owns the land and is intent on harvesting the timber or farming, there is a financial incentive to maintain proper land maintenance. Otherwise, profits could literally go up in smoke.

The federal government might own the land out west, but it is the environmental radicals that control it.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Endangered Species Act (ESA) have more to do with the increase in the intensity and size of forest fires more than anyone cause. Both were established in the early 1970s. As noted above, it only took a decade to reverse generations of hard work.

The ESA was enacted to protect animals on the verge of extinction. A problem occurs when radical environmental groups sue, under the ESA, to stop forest management practices, such as brush clearing, controlled burns, or logging. The northern spotted owl is the perfect example.

In the 1990s the owl was listed as a threatened species, whose habitat range includes northern California, Oregon, and Washington. A 1991 court order put a halt to logging national forests in those states, for fear of disturbing the habitat. Following the court ruling, logging decreased sharply. The amount decreased by so much that logging on federal lands has decreased 75 percent since 1990.

The decrease in logging is an ecological disaster. When the government is not allowed to remove dead trees and underbrush, it is bound to become fuel for a fire. The dead tree situation in California is an abomination. Late last year, the U.S. Forest Service, Cal Fire, and the Tree Mortality Task Force announced there was a record 129 million dead trees and warned of the danger posed by the excess fuel.

There is good news on the horizon, however. Secretary of the Department of Interior (DOI) Ryan Zinke is working to make the federal government more efficient in its management of forests. Recently he announced a reorganization plan for the department to place more resources and personnel out west, including giving the regional managers more responsibility to act. Zinke wants more personnel in the field and wants them to be able to make decisions, instead of having to wait on D.C. for permission to do anything.

Zinke recently tweeted about the fires out west, “Fires across the west are burning hotter and more intense. The overload of dead and diseased timber in the forests makes the fires worse and more deadly. We must be able to actively manage our forests and not face frivolous litigation when we try to remove these fuels.” But the Secretary can only do so much; Congress must also act.

So far, half of Congress is moving on the issue. Rep. Bruce Westerman (R-Ariz.) introduced, H.R. 2936 The Resilient Federal Forests Act of 2017. According to the House Committee on Natural Resources, “the bill streamlines onerous environmental review processes to get work done on the ground quickly, without sacrificing environmental protection. The bill also minimizes the threat of frivolous litigation by providing alternatives to resolve legal challenges against forest management activities.” The legislation passed the House on a bipartisan basis and sits in the Senate awaiting action. Hopefully, the intensity of the fires will force the Senate to move the legislation forward as a standalone bill or put it in the upcoming omnibus.

All this situation proves is that there is no one more dangerous to the environment than a radical environmentalist.

– – –

Printus LeBlanc is the Legislative Director for Americans for Limited Government.